I’ve gone fishing today. If we fail to catch fish, at least we’ll come home sunburned and exhausted.

Remembering Wallace

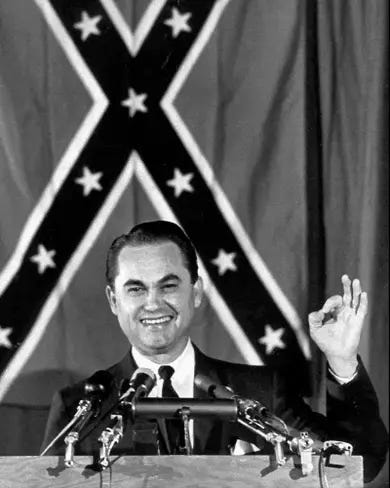

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

Those words echo in twentieth century politics. For many historians, they define an important epoch in American history. Of course, they’re merely one phrase from the fascinating and controversial life of George Wallace, long-time Alabama Governor.

I’ve known of Wallace for years. Any amateur student of presidential history couldn’t help but be acquainted with the four-time, failed presidential candidate. But many Americans remember Wallace best for the important role he played in the struggle for civil rights in the second half of the twentieth century.

Perhaps “important role” is too bland. Let’s be honest: Wallace is the poster boy for everything wrong in political attitudes toward civil rights. That is to say, he is seen as having been the foremost political opponent to the full equality of black Americans.

In Wallace’s inaugural gubernatorial address in 1963, he infamously declared: “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

The language of tyranny is important to understanding Wallace’s position. He campaigned in opposition to any federal imposition on the rights of states to determine best how to handle their affairs. Of course, such a view was bound to put governors and the federal government on a collision course after Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

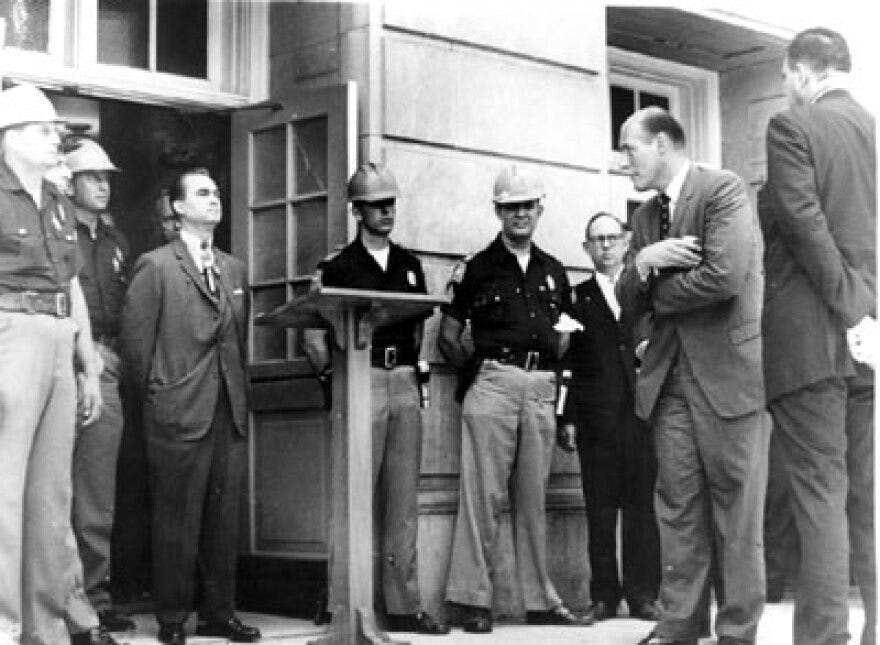

Wallace managed to claim the spotlight best with his defiance of the federal government’s order to integrate the University of Alabama. Just a few months after his inaugural speech, he stood in the doorway of Foster Auditorium to prevent the enrollment of James Hood and Vivian Malone, two black students. (Another black student had been accepted and attended briefly in 1956 but was expelled under dubious reasoning.)

Wallace argued that the Constitution granted states, not the federal government, authority over public institutions like universities. While under some legal views this was technically defensible, Brown and later the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it moot. It didn’t help that people could see that racial animus seemed to pervade the policies of those who claimed constitutional grounds.

The image of Wallace standing in the doorway remains an important moment in the history of civil rights. It illustrates, in extreme fashion, the many clashes between different levels of government over racial questions. Though he ultimately stepped aside after being asked to by Brigadier General Henry V. Graham (who was instructed to ask him to by President Kennedy), he parlayed his defiant stance into a presidential campaign. Wallace, having gained a national profile, cultivated an image as a principled patriot, a populist, and a bulwark against federal overreach.

Nevertheless, Wallace repeatedly used racist arguments, images, and tactics as he governed and campaigned. While real debates did exist during that period about how to achieve progress for black Americans, it’s impossible to explain away Wallace’s policies as simply being about “honest, intellectual disagreements.”

Note: Some argue that Wallace was a conservative populist (see Lloyd Rohler), but anyone who knows anything about the Southern Democrats in that era knows that ideological descriptions are complex issues.

More Than a Flash in the Pan

Some would argue that Wallace is merely a footnote in electoral politics. He did, after all, run unsuccessfully for president four times. He never even became the nominee for his own Democratic party. However, his influence mattered. As Stephan Lesher memorably put it, “George Corley Wallace was the most influential loser in modern American politics.”

Consider a few illustrations of this claim:

In his 1968 campaign, he ran as a third-party candidate for the American Independent Party. He garnered 13% of the vote and 46 electoral votes (winning five states). He came quite close to having the election tossed to the House of Representatives. It’s possible that his presence in the race changed the ultimate outcome of the election, though presidential historians debate this point.

Additionally, his emphasis on states’ rights created significant turmoil in both political parties as they began realigning, in part, around questions of race.

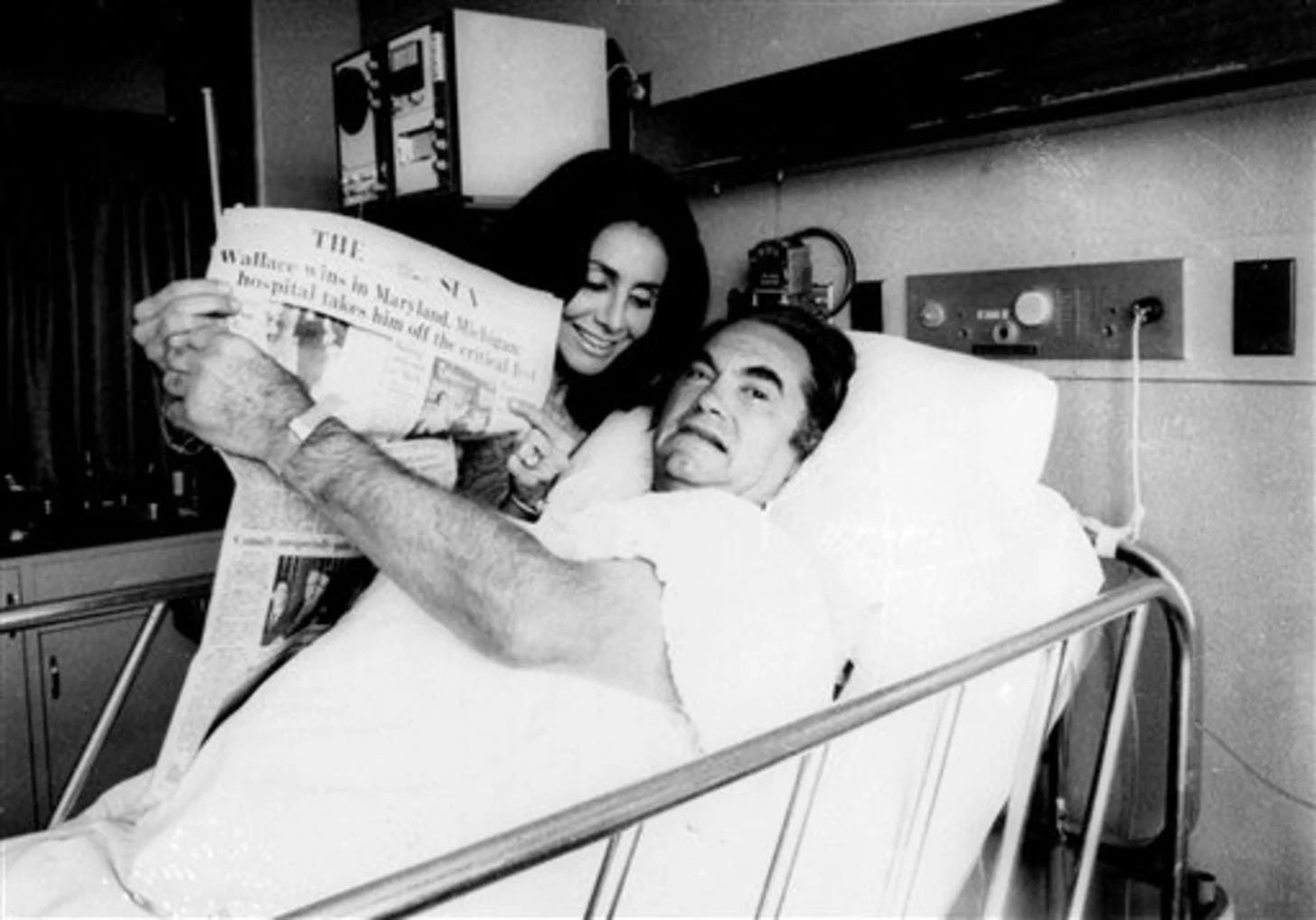

Wallace also had an impressive showing in his 1972 campaign. Though he lost the delegate count by a wide margin, he was barely two percentage points behind George McGovern, the eventual nominee. It’s impossible to know how things might have turned out had tragedy not struck (see below).

In terms of actual successes, Wallace is the longest-serving governor in Alabama history. He served four terms (1963-67, 1971-79, 1983-87), spanning nearly 25 years. Some argue that he partially served a fifth term as his first wife Lurleen stood for election (and won) in 1967. She would die of cancer just a little over a year into her term.

But Wallace has also left a legacy with his campaigning and rhetoric. While his appeals wouldn’t land with many today, some of the same concerns he expressed often and colorfully on the campaign trail have found their way into the campaigns of every major politician from Nixon to Reagan, from Bush to Clinton, from Trump to Biden.

What I Didn’t Know (and Why)

A recent podcast is what nudged me into my inquiry of Wallace. I listen to so many that I honestly can’t remember which one. Either the host or a guest spoke of the capacity for people to evolve and change when it comes to views on race. Then in passing they mentioned George Wallace’s attempted assassination, followed by his later views on race. I scratched my head, thinking there’s no way I could have missed the fact that Wallace had nearly been killed by an assassin, having been shot four times while at a campaign event in Maryland. He was paralyzed from the waist-down. (He is the only person to candidate for president from a wheelchair besides FDR.)

I was shocked to learn that this turned out to be a turning point in Wallace’s political career. While it took time for him to make the full turn, he publicly sought forgiveness from the black community in Alabama for his earlier views and policies before running for governor the final time in the 1980s. Most memorably, he addressed the Southern Christian Leadership conference (of MLK, Jr. fame) in 1982. He said, “I did stand, with a majority of white people, for the separation of the schools. But that was wrong, and that will never come back again.”

When Wallace ran for governor the final time, he promised black Alabamians more jobs and equality. They believed him; he won the race with 90% of the votes cast by black citizens. During that term, he appointed 160 blacks to state governing boards and pushed for greater black voter registration. Registration doubled.

Of greatest symbolic significance, Congressman John Lewis who had been viciously beaten in the 1965 civil rights march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge (in Alabama, of course), publicly forgave him.

Wallace’s sincerity, of course, is questioned. Politicians are known for shifting with the winds when it suits them politically. One author says that these changes were not only triggered by his brush with death in 1972, but a born-again conversion experience in 1979. Diane Bernard captures the tension surrounding his legacy well:

Fifty years after his shooting, Wallace’s tangled legacy remains the subject of intense debate. Some observers say the governor deserves forgiveness because he made amends with the very people he had wronged. (Civil rights icon John Lewis, for his part, publicly forgave Wallace in a 1998 New York Times op-ed.) But others see Wallace as an irredeemable villain.

It is a raw subject for those who lived through this period. After all, Alabama was the center of so much conflict and violence. The bus boycott sparked by Rosa Parks happened in Montgomery. The Selma March was an Alabama affair. And the fatal bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church happened in Birmingham.

But I return to my main question: how had this fascinating turn in Wallace’s story escaped my attention? After all the documentaries, biographies, social and political histories and more that I’ve read or seen from this period, why have so few of them considered this later period in Wallace’s life? Why have so many altogether ignored it? Why are we only left with an image of a man living in the past?

There is no clear answer. It could be that a normal person will always miss details, even when looking at the same period on multiple occasions. I’m sure that’s a significant reason for the oversight. However, I can’t help but wonder if another tendency in modern discussions of politics and race may be partially to blame.

We want people to change their minds when we think they’re wrong. But we’re slow to forgive, while quick to doubt their sincerity.

More specifically, people think that if you agree that racism is a problem, you must agree on the scale of the problem and the solution to it. Otherwise, you must not be sincere.

One could be forgiven for having trouble with Wallace’s apparent conversion (both spiritually and politically). He did, by many accounts, treat all three of his wives poorly. And many politicians have been known to evolve on social questions when it served them politically.

It must be noted that Wallace was much more muted on questions of black equality and segregation during his first run for governor in 1958. He was of a mold of political leaders more open to progress in these areas, until it cost him election. Wallace’s opponent buddied up to the Ku Klux Klan. Wallace, who had the backing of the NAACP, looked compromised. It’s a well-documented fact that Wallace responded to his defeat by saying, “I was out-niggered, and I will never be out-niggered again.”

When one puts Wallace’s political-ideological arc in perspective, one could argue the case several ways:

First, Wallace was always an unrepentant racist. He didn’t campaign on his racist views until after being mute on them didn’t connect with voters. Later in his career, when the tide was shifting on such issues, he exploited an opportunity to “convert” publicly and get with the times.

Second, Wallace was just a political opportunist. When he thought racial ideology (pro-segregation, and sometimes white supremacy) wasn’t salient, he avoided it. When he thought they suited him, he advocated for them. When they were growing toxic nationally, he “repented” of them.

Third, Wallace is a complex man from a complex era. Wallace did evolve in his views of race, though this evolution was combined with his own upbringing in the poor, rural south, internal contradictions inside the Democratic party, personal crises, and some degree of spiritual awakening.

Readers won’t be surprised to learn that I favor the third interpretation.

Two Takeaways

First, every Christian should change in some ways over the course of following Jesus. Change is the central dynamic of sanctification. While there isn’t always a direct line between spiritual change and political ideology and preferences, there are connections.

Christians should privilege the kind of changes that issue forth in spiritual fruit. That is, after all, the category of change the Bible focuses on. Yet even peace, joy, and longsuffering take on shape in actual human lives, circumstances, and social periods. We should expect growing Christians—which includes thinking ones—to reconsider some positions. They may not be radical changes from their initial starting points, but it seems an unavoidable corollary of growth, thought, and the application of timeless principles across generations.

At the same time, “changes in minds” can sometimes occur suspiciously close in time to other changes in circumstances. We should be skeptical of our own hearts, wondering if these changes stem from discomfort in carrying our cross. But neither should we cynically doubt all changes in our brethren. Our finitude and fallenness mean that we are wrong about some things, whether through rebellion or ignorance. We need each other to help grow in obedience and knowledge.

Second, we live in a world that is both pro-change and pro-cynicism. People of all political stripes club others with contradictory claims: “You’re wrong! We’re right.” When others occasionally start to reconsider their views, we cast doubt on their motives. Or worse, we try to weaponize their changes against them: “Look at them: now they’re flip-flopping!” Certainly, flip-flopping is a real thing. (I’ll resist a pun about the first day of summer here.) But sometimes flip-flops are just another way of saying, “I was wrong, and I’ve changed my mind.” I do think some of the cynicism could be tamped down if people would just come out and admit that, but I digress.

Wallace’s biography is one that still merits consideration as we try to understand what was happening in American politics over a tumultuous, four-decade period. But it’s also instructive for observing how messy (and barely decipherable) some people’s views are over time. We may not be able to figure them out, but they should be a reminder to us about (1) telling the whole story, and (2) appreciating the nuances of changes in perspective.

Sources Consulted:

Diane Bernard of Smithsonian Magazine.

Richard Pearson of The Washington Post.

Marshall Frady, Wallace.

Stephan Lesher, George Wallace: American Populist.

Lloyd Rohler, George Wallace: Conservative-Populist.

Follow Up:

Father’s Day was two Sundays ago, but I’m still thinking of Joel Miller’s recent piece, “My Dad Gave Me Books—and More Besides.” Take a moment to enjoy its warmth and brevity.

Currently Reading:

Catch-up week

Quote of the Week:

“There are times when God graciously pours part of our future reality into our present-day experience and provides radical healing and deliverance. Such occasions dramatically demonstrate God’s power over other forces in our lives. We give thanks to God when this happens. But God is also glorified as we learn to rejoice in him even when affliction remains and change seems to be very slow—or when it feels as if we are even going backwards.”

Sam Alberry, Is God Anti-Gay?

On My Mind (New Feature):

In this new feature, I’ll offer a brief claim, comment, or question that’s on my mind. It’ll be something I may pursue (or have pursued) in prior newsletters or essays, or it may just be a one-off type of thing. This feature simply allows me the chance to get something out there that may not be fully formed, but potentially may be substantial enough to provoke some reflection or conversation.

Senator Tim Scott’s candidacy for President is something I admire and support, but it’s hard for me to get excited given the insanity that prevails among likely voters. I appreciated this quote by Erick Erickson, but I’m don’t know that it guarantees traction.

“The left really fears Scott. The left has told black voters for years that they are victims of systemic racism and that without the Democrats, they cannot get ahead. Tim Scott tells black Americans that they too can get ahead if they work hard and stop believing they’re the victim and America is racist. There are racists in America, but the country itself is not.”

Read the whole post here.