This week I’m attending the Missouri State Association in Springfield, Missouri. This year, Faron Thebeau and I will be presenting a seminar entitled, “Serving Storm-Tossed Families,” based on Russell Moore’s excellent book on the topic. I’ll also be participating in a panel discussion of ideas for renewing local associations.

The Painful Reality

I occasionally read Joel Miller’s Substack, Miller’s Book Review. I enjoy about every third or fourth post, but since I discovered him back in December or January, one post has lingered with me: “Keep or Toss? My Personal Criteria for Culling a Library.”

“Cull” is an interesting word. It’s not a word many people use often unless they’re raising livestock. “To cull” means to select from a large quantity, but it’s usually linked specifically to the slaughter of animals. (Don’t worry. We’ll get to libraries in a moment.)

Merriam-Webster states this meaning of cull as “to reduce or control the size of (something, such as a herd) by removal (as by hunting or slaughter) of especially weak or sick individuals.” Anyone with rural sensibilities can appreciate the conservative, agrarian context. It perhaps explains why so many vegans reside in urban, densely populated metropolitan areas, while the decidedly non-vegans (who are enthusiastic about their non-veganness) more often dwell in rural, less-populated regions.

Simply, sometimes populations need to be thinned out for the greater good of order, stability, health, and ecological balance. Now think about all those books lining your shelves. What needs to happen there?

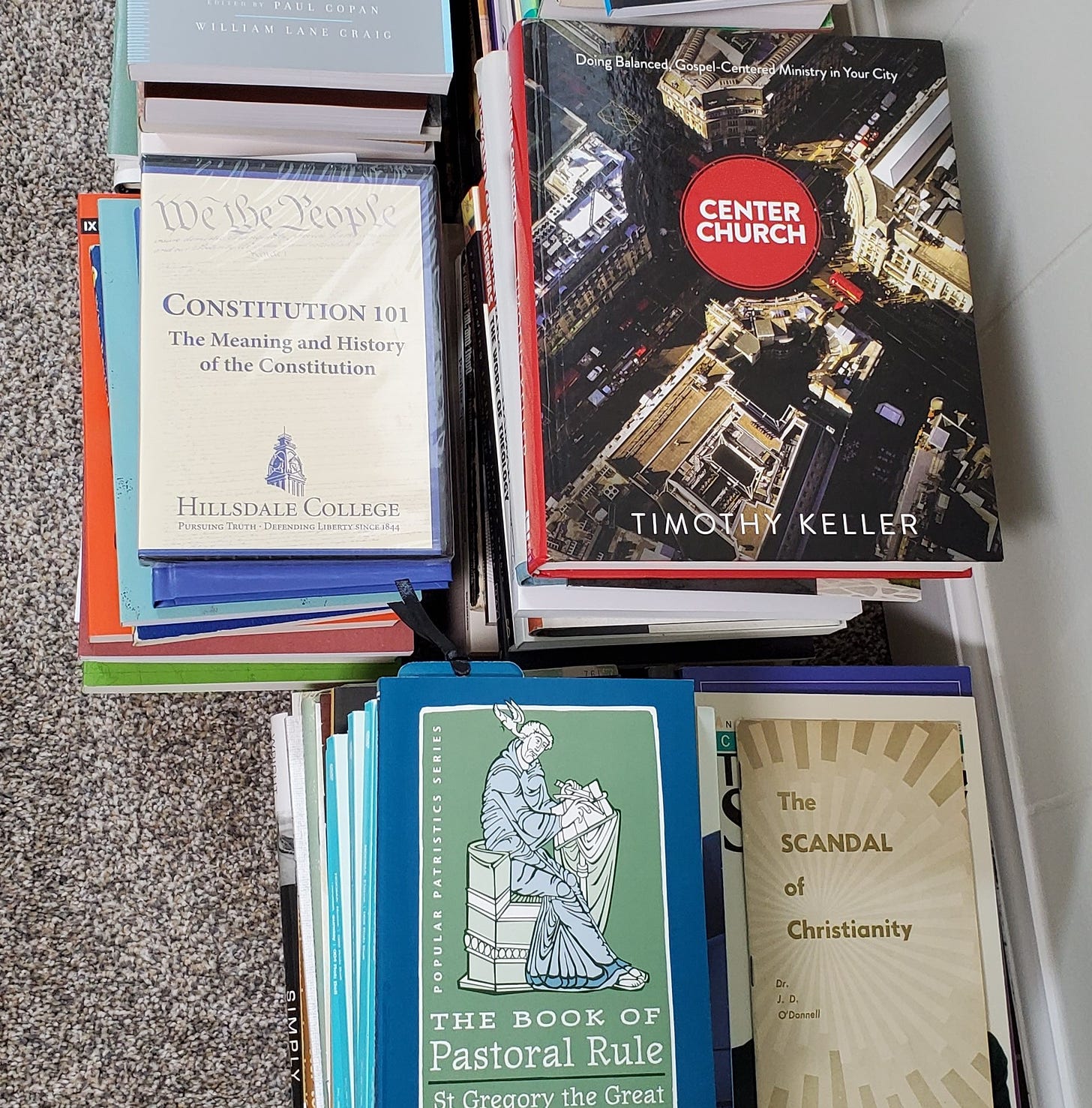

In an earlier newsletter I discussed the renovation project in my study at the church. Though I had a new bookcase constructed and built into the wall, I’m still limited on space. I resolved not to have stacks of books lining corners of my study or cluttering my desk (well, maybe 10 or 12) once I moved back in. I refuse to have more than three bookcases in my office. (I have two standalones also.)

Initially I thought I’d only have to cull 20-25 books. As things have unfolded, I’ve been disturbed to learn that the number is closer to 60. After all, with some books still lying helplessly on the floor, awaiting a spot in the bookcase, decisions must be made. Where to begin?

As best as I can tell, most of my subscribers are avid readers. Some have massive collections. I suppose mine would skew on the mid-larger side—call it 1500. I thought a couple of years ago that this was too many, yet the collection continued to grow. Were space not a factor, and were I actively engaged in an academic or literary career, I might feel differently—though I doubt it. At a certain point, one exhausts their ability to use such a collection profitably.

Not Just What, but Why

The process of culling books, the total of which perhaps comes to 45 at this point, has been more instructive and painful than I could have imagined. I’m finding that before one develops clear criteria for determining what to part with, it helps to ask deeper questions about their books. One must ask not just what (title, topic), but why.

The why evokes a deeper reality: there are different reasons why some of these books are on your shelf today, which provides some clue to their most appropriate future home.

There’s the book you had to buy for a course, but the professor didn’t require you to read it and/or didn’t test you on it.

There’s the book your in-law gave you, thinking you’d really enjoy it.

There’s the book you thought was a steal when you acquired it from the free book cart at the seminary library.

There’s the book you marked up extensively before you really knew about book darts.

There’s the book you bought because it was 50% off at the conference and looked important.

There’s the book you bought but haven’t read because all intelligent people have it on their shelves.

There’s the book a favorite professor of yours wrote and autographed.

There’s the book that changed the way you think about topic x.

There’s the book that you’ve read three times, given away copies of, and recommended countless times.

There’s the book you contributed a chapter to.

There’s the book you reference in lectures, lessons, and sermons often.

On Criteria

I don’t see these descriptions as criteria as much as an honest set of acknowledgments about the background and significance of these books. They might function as a sort of criteria for discerning the relative value of things.

For example, most readers can tick through the list above and discern a probable pattern: from less worthy reasons to keep books to more worthy reasons. Generally, I think that’s correct. Yet it’s still difficult.

Sometimes professors write books that aren’t all that great. They taught you, and you liked them well enough. So, sentimentality is what keeps their title lodged on your shelf. You will see this as a more or less justifiable reason to retain the book based on how valuable you think sentimentality is as an emotional-mental state or spiritual virtue.

In a different way, maybe the book you have just because all intelligent people have it is yearning to be read. Don’t get rid of it; you weren’t crazy for purchasing it. Just go ahead and read it finally!

I have found that confronting my collection with honesty (and it’s still a struggle) has helped me make progress in producing a more excellent one.

In the aforementioned article, Joel Miller raises eight questions that have helped him make decisions about culling his library. Below I have reposted his questions in bold, and included my own explanation/gloss in parentheses:

1. Am I finished with this book? (You may no longer need it if your project is complete.)

2. Do I need this book? (How likely is it that you’ll use it in the future in a meaningful way?)

3. Can I easily get another copy? (Depending on how expensive and/or rare it is, it could affect your decision.)

4. Do I love this book? (An emotional or sentimental attachment affects things.)

5. Does this book represent an important shift in my thinking? (Just the visual presence of a book on a shelf can be a powerful reminder of how we’ve grown or changed.)

6. Do I enjoy dipping back into it? (The book brings such joy that you return to it often.)

7. Is it part of a set? (It’s hard for some to break up a collection, but perhaps only select volumes are good/useful/important.)

8. Am I tired of thinking about this? (Especially for those who’ve done research degrees—especially in fields you don’t necessarily work in—it may be time to move on. I think about the doctoral student in philosophy who lingered in ABD land for too many years, and then offloaded a lot of primary sources on me about 15 years ago.)

These are quite helpful in getting one started. I can immediately think of where these questions paraded through my mind as I scanned my shelves and stacks. Some of them are obvious like #1. Some are more intuitive like #8. Together, they’re strong.

I’ll add a few additional criteria, some of which relate to Miller’s, but in my own wording:

1. How likely is it that I will ever read this book?

2. How likely is it that I will ever pursue that writing project that I’ve kept a book like this around for?

3. Do I know someone who would appreciate and use this book more than me? Why not give it to them?

4. As an extension of #3, would the church library be better served by this lay-level book on spirituality, or is it such a classic that I must have my own copy?

5. Is this an important, bad book, or an unimportant, bad book? (If the former, then keep it. If the latter, then toss it.)

You Can’t Take Them with You

Church people are always good at quoting the biblical truth: “you can’t take it with you.” Yet we live out of line with this principle in so many respects. We do so with respect to things which accumulate in our garages, attics, basements, closets, and yes, on our shelves. At some point we have to decide when we’re going to push back. Readers—who often style themselves as “thinkers”—are obliged to do the same.

Man is not saved (nor helped) by book acquisition alone.

Follow-Up:

In Newsletter #68 I reflected on war films (and a particular war film) which I had seen recently. I had begun reviewing my list of favorite war films of all time with the intention of sharing. Brett McCracken beat me to the punch (somewhat) in this recent article, “21 War Films Celebrating the Virtue of Sacrifice.”

I decided to share my list of top 10 favorites. Mind you, I’m not saying these are the best. “Favorite” and “best” aren’t the same, though they often align. With that caveat in mind, here they are (in no particular order): 1917, Saving Private Ryan, U-571, Sergeant York, Hacksaw Ridge, Zero Dark Thirty, Dunkirk, The Imitation Game, Thirteen Days, The Patriot. Plenty of honorable mentions, but these are my top ten favorites.

Currently Reading:

Vern Poythress, Inerrancy and the Gospels: A God-Centered Approach to the Challenges of Harmonization.

Abraham Kuyper, Common Grace (Volume 1): God’s Gifts for a Fallen World.

Quote of the Week:

Here's a definition of good productivity: good productivity minimizes distraction, unproductive tasks, inefficiency, and procrastination so you can excel professionally without damaging your family, health, or spiritual life. I often see creative professionals - especially writers - spend much of their working lives behind schedule, missing deadlines, and laboring under constant frustration that they need to be getting more done. Yet at the same time they often are "working" all hours of the day, late into the night, and on weekends. Those with families sometimes find that mom or dad is always fiddling with work and unable to be fully present with their spouse or kids. They don't sleep enough, get adequate exercise, or spend time in recreation. I see good productivity as a solution to these unhealthy patterns...Productivity is not, fundamentally, about getting as much work done as possible. It is about eliminating wasted and inefficient work time, so that you can attend successfully to your work, family, health, and spiritual life.

Thomas Kidd, “What is Productivity for?”