Who are you reading these days? Journalists? Theologians? Poets?

How are you reading them? Printed books? Print magazines or journals? Ejournals via digital download on your e-reader?

Just as important, where are you reading them? Who is amplifying their voice in order that it can reach you? Is it the New York Times Editorial Board, Zondervan Academic, Yale University Press, or Twitter/X?

All these questions are important and interrelated, but this last one is fascinating to consider in our present media ecosystem. The landscape has changed so drastically in the last few years, not to mention my lifetime. (For readers older than me, I cannot imagine how dizzying this whole transition has been for you!) Those changes involve technological innovation, changing economic/profit models, the shifting Overton Window in American culture, and the elusive thing called “the public interest.” Even when we know these factors are at work, it’s quite difficult to forecast how our intellectual climate will change over time.

I’ve mentioned on several occasions that I think it’s more important to admit when we were wrong as it is to point out when we were right. Well, let me tell you my biggest error when it comes to predicting the future.

It’s the early 1990s. I’m in the third or fourth grade, and it’s “library day.” I loved library day. On this library day, the librarian, Mrs. Penny Kemp, was demonstrating this newfangled thing called “the Internet.” I still can see the Netscape Navigator icon slowly shimmering as something mysterious was happening. We waited and waited. Finally, we were shown how this Internet thing could allow us to send this invisible correspondence called “email.” I wondered, “Why would anyone want to communicate like that?”

Needless to say, I was thoroughly underwhelmed by the demonstration. I still remember thinking to myself, “Yeah, this isn’t going to amount to anything.”

I was wrong. Epic fail!

Return to my question above. How do you read what you read? An author (“A content creator,” they’re increasingly called) articulates himself in words. But a publisher amplifies those words in a context and/or on a platform. “Publisher” here can be interpreted very, very broadly. On one level, this can be anything from the individual to a global corporation. They choose to release the author’s message to the world. On another level, publishing can involve editorial oversight, logistical support, and the financial backing required to get that message to its intended audience. Publishing, then, is a multi-faceted enterprise.

Publishers of all sorts are subject to goals, policies, audiences, profit margins, shareholders, and countless internal and external pressures. Even if technology could somehow remain static, these other factors would influence what publishers chose to publish.

One other important caveat. Publishers are dealing with a wide range of literary forms. These include news journalism, opinion columns, novels, poetry, textbooks, user manuals, and at least a few dozen other literary artifacts. Thus, the standards, economics, and models differ depending on what is being published.

My concern is two-fold. First, it is increasingly difficult to find trustworthy sources of information whose voices can sustainably provide what we are seeking. Second, discerning readers will have to work as hard as they ever have in order to identify trustworthy voices and enable healthy incentive structures that reward good writing.

If there was ever an indication that people were hungry for good writing, regardless of the subject or form of writing, see Substack.

Substack was founded in 2017 by Chris Best, Jairaj Sehti, and Hamish McKenzie. It is by no means the first online platform for a wide range of “content creators.”

Most readers will be familiar with Wordpress. (I myself have been involved in three different ventures that used Wordpress.) Frankly, most of us have been reading Wordpress sites for years, and in quite a few instances, not even recognized that it was a Wordpress site.

The significance of this is two-fold. First, it speaks to how successful Wordpress has been in allowing mostly amateur writers to find an online home for their writing. Second, the appearance of respectability and the ease of functionality is especially important for people who are engaged in the risky venture of amateur writing.

Let’s face it: when someone tells you they have self-published a book, you often have to resist your gag reflex. It’s not that self-publication necessarily means the work isn’t well-written, truthful, or even excellent. However, it typically implies several hard truths. First, the author didn’t take the time to submit their manuscript to publishers for consideration. Or, if they did, the publisher(s) rejected it. Second, the author probably didn’t take the time to have a professional editor proofread the work. Third, the author likely didn’t participate in any kind of external review, fact-checking, or the like. And fourth, well, you get the point. There are exceptions to these rules, but these generally hold true.

Now take this skepticism that we, the general public, have toward self-published books and apply it to something like a blog. Note that we don’t even call it a website, a journal, or a column. We call it a “blog,” even if, strictly speaking, the online content may not best fit the conventional definition of a blog. As a writer, you’re in an uphill battle for credibility.

To be sure, writers of all kinds ought to earn trust. They should be willing to do the hard work required to achieve credibility. Yet we are living in a time when the traditional publishing world is unwilling to take chances on certain kinds of writers, stories, and projects. Thus, those with a sense of calling to writing are obliged to seek out avenues to advance the stories and projects they think there’s an audience for. This is why I appreciate what Substack has accomplished over its short time in existence.

Some of the best and brightest have left established media institutions for Substack. Some unknowns have been “discovered” due to their presence on Substack.

Frankly, this is a big reason why Churchatopia is a Substack publication. In 2020, after ten years with the Helwys Society Forum (Wordpress platform)—a site I helped found with two other good friends—I felt like it was time for a change. I spent much of the end of 2020 and first half of 2021 thinking of what a new writing venture might look like. I had a few projects in the hopper, but nothing that would occupy me in an ongoing way.

In this general timeframe I was increasingly noticing that some of the very best writing I was enjoying wasn’t to be found at The New York Times, The Washington Post, or The Wall Street Journal (although I happen to like the WSJ). It’s not that these traditional newspapers never published good things. It’s just that the price wasn’t worth the paucity of good journalism. Moreover, I found that such publications refused to deal with some of the legitimate and often politically incorrect issues of our time. From trans issues to COVID-responses to the ethics of procreative efforts, these publishers were mum.

Meanwhile, a burgeoning number of writers—whether scholars, journalists, former politicians, and more—were appearing on Substack. Some were paid subscriptions, but most of them had a free option, allowing readers to take their time deciding whether they wanted to patronize a specific writer.

By January of 2022, I launched my newsletter/Substack page. Just a few months ago, I added a paid option, which, at this point, allows readers to comment on posts and access materials in my archive going back past 12 months. The paid option was added for two reasons. First, I was encouraged to do so by a satisfied reader. Second, I figured that if writing ended up being a bigger part of my future professional life, I needed to treat it more seriously as a possible revenue stream, a way to supplement my income, not knowing how my family’s financial needs may evolve and increase over time.

I’ll be the first to say that I don’t have high expectations concerning income from Churchatopia. That was never on my list of motivations for launching this online venture. Moreover, readers (myself included) have to be very choosy when it comes to which writers we patronize. Some depend on it for their living, and they provide a LOT more than what I provide. There is such a thing as a professional writer. While I aspire to the literary standards of a professional, a professional I am not!

In reality, Churchatopia was about opening a dialogue between myself and whoever else happened to care about many of the kinds of topics I care about. It was about forcing me to write on a weekly basis, which is a bit more than I was writing prior to Churchatopia. It was about allowing me to explore some subjects in some ways that I felt would be interesting, truthful, and helpful. If the majority of my readers would characterize my work as “interesting, truthful, and helpful,” then I’ve succeeded.

Part of this exploration into the world of online writing has been to help readers understand a bit more about some of the dynamics, constraints, goals, and motivations of online creators. However, I hope this information has a collateral effect as well. I hope you will seek out some of the great Substack-based authors whom I’ve benefited from and support their work. I subscribe to over a dozen Substack author pages, and have had up to four paid subscriptions at one point.

What you click on matters. We live in the so-called “attention economy” where the number of seconds spent on a webpage and the items clicked on generate massive revenue. Often, this revenue incentivizes people who aren’t engaged in serious writing. (There’s a reason they call it “clickbait”!) As Christians who care about God’s institutions—the home, the church, and the state—we recognize that our work is strengthened when we participate in the strengthening of other legitimate vocations, writing being one of them. Good writing deserves to be rewarded.

May I illustrate the impact of platforms like Substack? Below is a list of the best, most significant articles I’ve read over the past week:

Jessica Testa and Benjamin Mullin, “Substack’s Great, Big, Messy Political Experiment.”

Ross Douthat, “Trump Has Put an End to an Era. The Future is Up for Grabs.”

Joel J. Miller, “The Books You Come Back to.”

Lisa Selin Davis, “Oregon is Writing Gender Policy with Blinders On.”

Jeff Shafer, “Machine Antihumanism and the Inversion of Family Law.”

Three of the five are from Substack sites/authors. One of the other two is a NYT article about Substack. The other is by a NYT op-ed columnist. The percentage speaks volumes.

Moreover, there’s a ton being written these days about AI, new technology, and the media landscape. As one who follows such developments, what would I say is the best tech criticism site? Mike Sacasas’ the Convivial Society, on Substack.

The best independent coverage of the transgender wars? You guessed it, Substack. See Lisa Selin Davis, Jesse Singal, and Jamie Reed.

The two best news coverage sites? The Free Press and The Dispatch. The first is a Substack, the second began as a Substack. By the way, compare the growth of their subscriber base and revenue with the legacy news media. It says a lot.

My favorite site on practical parenting? Katherine Johnson Martinko’s The Analog Family, on Substack.

Where is much of the fair and nuanced political coverage anywhere? You guessed it.

As the New York Times’ piece above puts it, Substack prizes itself as a home for “cogent analysis and civilized discussion,” unlike Facebook, Twitter/X, cable news, etc.

There’s a reason why Elon Musk attempted to purchase Substack over a year ago. He’s a complicated, strange person, but the man has an eye for impactful projects and enterprises.

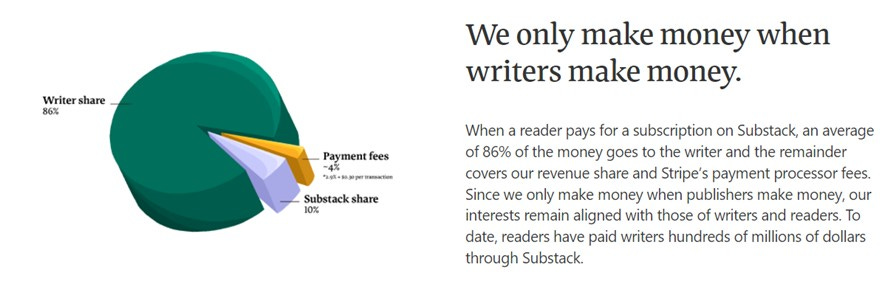

Some of these developments in the arena of online publishing are a function of what Ted Gioia (another fascinating Substack writer) calls the Macroculture versus the Microculture. The macroculture represents massive corporate interests, political correctness, ideological homogeneity, and the like. The microculture represents the grass-level pushback from creators who, after all, generate profit for the big guys (along with ad revenue). Meanwhile, Substack has provided a home for those creators and puts most of the profits from their labor back in their pockets, creating sustainable pathways for good work to be rewarded. They only take a 10% cut of subscription revenue.

It would be easy to focus on the fact that more than 30 Substack publishers earn at least $1 million annually. But it’s the folks who generate $10,000, $30,000 and $100,000 per year that is most impressive. These are smart, capable writers trying to supplement their incomes, as well as full-on professionals who have made writing their careers. This isn’t even to mention those Substack publications who have paid writers on staff, and encourage them to do the kind of journalism NBC, ABC, CBS, or The Washington Post would never let them do.

I confess: I don’t understand how all of this works. The economics, the ideology, the technology—it’s a fascinating mix. Substack isn’t a perfect company, but they seem to be on the right track.

Bottom line: we need to patronize the creators and institutions worthy of our support.

It’s easy to tear things down. It’s very hard to reform things. It’s nearly impossible to start new things that will stand the test of time. We need to remember these truisms soberly, whether we’re thinking about information consumption, business start-ups, church revitalization, or church planting. We should support what matters and recognize the ways in which we may be complicit in malformed financial incentive structures.

Your attention is valuable. Only give it to who and what matters.

Follow Up:

In Newsletter #139, I listed a handful of my favorite Theological Symposium papers through the years. In passing, I mentioned that Joshua Colson was perhaps the best Free Will Baptist writer under the age of 30. Well, when I wrote that I knew it was a statement deserving of some provisos. For one, there could well be better ones whose work I simply haven’t read. Moreover, I was thinking primarily of men, since they constitute the lion’s share of published writers in my circles.

So, in the interest of being more exact, let me say that Rebekah Zuniga is perhaps the best female author under 30 in my circle, and one of the best ones overall. Here’s just a small sample of her work over at the Helwys Society Forum.

Quotes of the Week:

Holy Writ is set before the eyes of the mind like a kind of mirror, that we may see our inward face in it—for therein we learn the deformities, therein we learn the beauties that we possess; there we are made sensible what progress we are making, there too how far we are from proficiency. It relates the deeds of the Saints, and stirs the hearts of the weak to follow their example, and while it commemorates their victorious deeds, it strengthens our feebleness against the assaults of our vices; and its words have this effect, that the mind is so much the less dismayed amidst conflicts as it sees the triumphs of so many brave men set before it. Sometimes however it not only informs us of their excellencies, but also makes known their mischances, that both in the victory of brave men we may see what we ought to seize on by imitation, and again in their falls what we ought to stand in fear of.

Gregory the Great (credit to Matthew Lee Anderson for bringing this to my attention)

When John and John Quincy Adams protested, in turn, the power of image over merit, and men over lawful institutions, they regarded personality as an illegitimate political force, a psychological tool designed to stimulate vulnerable citizens’ desires. All humans craved notice, fame, renown; if they could not attain it themselves, they found an object to worship vicariously. In that sense, democracy was about representation, which required a certain theatricality, or, as John Adams put it, “glitter.” He bemoaned the fact that candidates had to promote themselves and “make the mob stare and gape.”

Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein, The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Culture of Personality.

The Reformers and their theological heirs did not conceive of the sufficiency of Scripture in isolation from the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in and through the written Word. Scripture is sufficient because it is God’s Word, inspired by God’s Spirit. But that same Word, inspired by the Spirit, is accompanied by the ongoing work of the Spirit Who illuminates Scripture by working in the hearts and minds of men and women. In this way, God continues to speak by the Spirit through that which He has spoken by the prophets and apostles.

Jesse Owens, “The Spirit and the Sufficiency of Scripture.”

Books I’m Reading Now/Still/Again:

Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein, The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Culture of Personality.

Timothy Keller, Making Sense of God: Finding God in the Modern World.

Ronald Nash, Faith and Reason: Searching for a Rational Faith.

Parting Shot:

I pride myself on being consistent with this newsletter every Monday morning, with very few exceptions (Typically, only vacations and major holidays). So, I should therefore note that there’s a reasonably good chance that I won’t be publishing a newsletter next Monday in view of the long holiday weekend, an extremely high workload, and some major church transitions. However, you never know! You can check your inbox next Monday morning and see if something is waiting for you or not.