Now let me give you another side of the story.

More than Sundays

More than one author has helpfully reminded modern readers, Christians especially, than liturgy is more than just what happens on Sundays. It permeates every area of our lives.

This claim assumes that we haven’t defined down liturgy as “stuff you do in Christian worship on Sundays.” Instead, we should understand liturgy to be principally about the rhythm and structure of ritualized practice, which includes everything from postures to language to adornment.

Rituals are “meaning-making” in nature. I think a lot of Christians assume this means, “Actions which have some kind complex message attached to them.” This is certainly true of some rituals. Think of the Lord’s Supper. In partaking (and continuing to partake), we proclaim Christ’s death until He comes. Our ritual actions are communicating something to the unbelievers who may be present, and they are reinforcing in believers the truths to which the Supper points.

This is a crucial type of “meaning-making,” but I think it’s fair to say that most liturgiologists emphasize other, less cognitive forms of meaning. Think of the emotional, psychological, communal, and cultural significance of ritual action, and how these give rise to what we label “meaning.”

We need not pit the cognitive against the non-cognitive. Both matter, and both are implicated in various liturgies.

A question of liturgy that then arises is more about the where and not the what. Defining liturgy as I have above means it is in no way limited to strictly “religious settings.” What, then, are the liturgies of the classroom? The liturgies of the workplace? What are the liturgies of our family’s week? And yes, what are the liturgies of sports?

One reading of last week’s newsletter might peg me as indifferent to my favorite teams when they’re having average or below average years. Far from it. I always wish that they would fare better than they are. However, that’s distinct from my willingness to sit for two or three hours and watch them flounder on the court or field.

In fact, what got me thinking about this point of liturgy was two things. First, I saw some brief coverage online of South Carolina’s women’s basketball. Second, I happened upon South Carolina’s athletic page when trying to get a piece of information. What struck me about both? The colors. The garnet and black, and sometimes garnet and white (depending on whether it’s a home or away game).

Those colors have been embedded in my aesthetic imagination since childhood. Even when I barely knew what football was, I would see them around my home and community. Though our family was a divided home (Daddy and brother rooted for Clemson, while Mama and I for South Carolina), garnet and black was often visible somewhere.

Do I love garnet and black due solely to exposure? Who knows? Why do I dislike orange so much? Does it have something to do with the fact that Clemson, South Carolina’s biggest rival, has it as their main color? I’m thinking it does.

Beyond Color

As I looked at a few images online I also saw the Gamecock’s beloved and nationally recognizable mascot, Cocky. Yes, a gamecock is essentially a glorified rooster. And Cocky looks like a big goofy chicken. But he makes me happy, so back off.

Cocky is just one piece of South Carolina Gamecock athletics. He’s surrounded by people with flags—one for the university, and one for the state. He celebrates success on the field and court with the cheerleaders and fans.

What about the fans? They know when to stand, and when to sit. (Sound familiar?) They know what to chant, and when to chant. They perhaps ought not run onto the field or court (see my last newsletter), but sometimes the spontaneity and euphoria of it is understandable. After all, if garnet and black elicit a wonderful feeling of familiarity, fondness, and fun, how much more does sitting in the stands do that?

We Are What We Do, Somewhat

Humans aren’t merely homo sapiens; they are homo faber. They are culture-makers. They create traditions, customs, art, and forms of play. They are, in fact, homo liturgicas. They create rituals, and then rituals create them.

Of course, this is part observation, part fascination, and part warning. To circle back around to some of my arguments for fair-weather fandom, we must be careful about being formed more as fans, and less as disciples. Fans can be fickle, foolish, and fanatical. Disciples are called to play the long game (pun intended). We commit to a lifetime of learning from and following Jesus. There is certainly joy in the journey, but a cross, too.

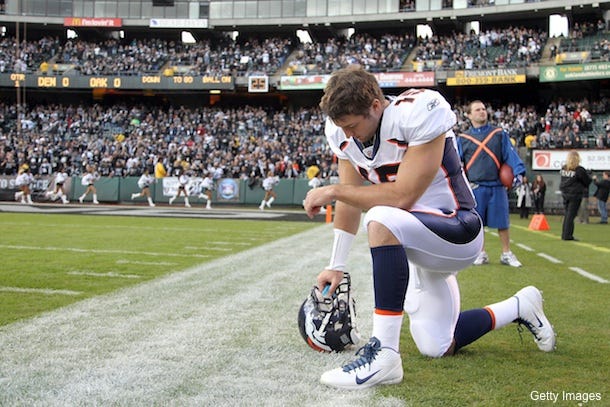

Perhaps one reason why we are so prone to integrate sports and Christian expression is because sports feel downright spiritual. Physical prowess and especially victory can bring a feeling of transcendence. Of course, I think there are more or less helpful ways for our faith to inform and direct our engagement with sports. (Never been a fan of “Tebowing.”) But I understand the impulse for people to integrate the two.

I think it’s healthier to imagine faith as the foundation, framework, and fuel of our lives. Sports, at best, should be a reasonably small room in the house. I suppose if you make your living in athletics, it might be a larger room, but you hopefully follow the metaphor.

The upshot is this: recognize how sports have formed and are forming you. Pay attention to their liturgical shape. Enjoy the game, but commit yourself to be formed most by liturgies of spiritual virtue, transcendence, and victory.

For Further Reading: Start with James K.A. Smith’s Desiring the Kingdom. Then check with me if you want to go deeper.

Follow-Up:

In my last newsletter I discussed fair-weather fandom, and especially the surprisingly good year that University of South Carolina men’s basketball team have had under the leadership of Head Coach Lamont Paris. Well, we learned last week that Paris had been voted SEC Coach of the Year. Congrats, Lamont! Shockingly, this is the third time a South Carolina men’s basketball coach has won this honor.

What I’m Reading or Rereading:

Melissa Kearney, The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind.

Murray Harris, Prepositions and Theology in the Greek New Testament: An Essential Reference Resource for Exegesis.

Quote of the Week:

Colloquially, “tell the truth as I see it” isn’t very different from, say, offering my “honest opinion.” (This is pretty much the opposite of the relativistic and romantic codswallop “my truth.”) And in most everyday cases, I think they’re probably interchangeable. But in my head at least, I see them differently. Telling the truth feels different than merely offering an opinion, because opinions don’t necessarily require a lot of fact-finding or rigorous thinking. Everyone has opinions. But a lot of those opinions are fairly free-floating, untethered from serious thinking and unconstrained by the ballast of facts. Telling the truth is different than offering an opinion. Because if you think you’ve actually got a handle on what the actual truth is, other people’s contrary opinions are, as a matter of logic, necessarily wrong. For instance, when I say that Dominion didn’t steal the election for Biden by switching millions of votes, I don’t think I’m merely offering an opinion. I think I’m telling the truth as revealed by a vast amount of evidence and the application of reason. That means people with a different opinion are wrong. It also means that some people aren’t merely wrong, they’re actually lying.

I’m the first to admit there’s a lot of shades of gray here. Not every dispute is as black and white. And that’s why I say, “tell the truth as I see it.” The “as I see it” allows for the possibility that I’m seeing things wrong or incompletely. It’s a concession to epistemological humility. I’m always open to new facts. I’m not always open to new opinions if they don’t come with new facts and arguments attached. Again, just to illustrate the point, I believe Hitler was a bad person, 9/11 wasn’t an inside job, America put a man on the moon, etc. I’m not open to any contrary opinions on these conclusions unless they come with some really startling new facts and arguments.

Jonah Goldberg, “I’m with Hur.”

Common Grace Wisdom (CGW): A Further Word about Poverty and Family Structure

Last week I called attention to yet another poignant book—in this case, a memoir—about the importance of family structure as it relates to education, poverty, and life outcomes. Rob Henderson’s discusses these in Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class.

Henderson has now appeared in numerous media outlets to discuss his recent title. You can see two of these discussions at the links below but pay close attention to the one with Jordan Peterson. Especially note minute-marker 3:29-10:47. Peterson and Henderson discuss his publicist’s inability to garner interest from many bookstores who typically have authors in for readings and book signings. So not only have many major media outlets and book-promoters refused to give this book much press, but they also systematically avoid books which cast any doubt on the claim that family structure is quite important.

As Henderson explains in one place, this is yet another example of a luxury belief. Overwhelmingly, the wealthiest Americans have generally themselves practiced traditional mores when it comes to marrying, having children, and remaining marrying. (Of course, there are always exceptions!) Yet many among the wealthy class have used their wealth and cultural influence to support messages and notions like “sex without consequences,” “abortion is good,” “marriage isn’t that important,” and so forth. In other words, “more traditional family life for me, but not for thee.” I encourage you to listen to either of the full interviews linked below.

The Psychology of Social Status and Class: Rob Henderson on the Jordan B. Peterson Podcast.

The Cost of Luxury Beliefs: Rob Henderson on the Glenn Show.

Parting Shot

Keep an eye out for a special post later this week concerning transgenderism.